Monday, May 27, 2013

Can a Story Change Your Life? - Character Study, Ad Infinitum: Infinite Ryvius (無限のリヴァイアス Mugen no Rivaiasu)

After over twenty years as an anime fan (the English-dubbed, black-and-white Astroboy being my first exposure to the genre), it's interesting to reflect on that fact that the same series has occupied my "all-time favorite" slot for nearly fifteen years. What's even more surprising is that it isn't one of the more well-known or critically recognized series: it's Infinite Ryvius, aka Mugen no Rivaiasu (無限のリヴァイアス), a Sunrise anime series from the very end of the 20th century - 1999, to be precise.

In a nutshell, it's William Golding's Lord of the Flies in space. (Maybe it should be ". . . in SPACE!") Yet as true as that categorization may be, the series is far from a mere genre-swapped derivative: I'd read and appreciated Golding's classic several years before Ryvius came along, but I never experienced the same catharsis from Golding's book that I felt from Ryvius. And that amped up effect isn't the sole product of its sci-fi milieu - though when I'm in the audience, it rarely hurts.

As with so many of the stories that I'll be featuring in the CASCYL series, Ryvius's strength comes from its characters. (This is a trend that should probably be expected, given my own penchant for character-centered storytelling.) And as seen in the picture above, its cast of characters is vast. While the largest growth arcs are reserved for the main cast, even side characters are affected just enough by the events of the series to hint at their unseen depths. The extreme circumstances force virtually every character to his or her breaking point at various moments in the series; but what compels the viewer to continue watching is how those characters react to those breaking points, and how those decisions then come to influence the overarching storyline.

Like Joss Whedon's Serenity, Ryvius plays to its medium's strengths. An expansively ensemble cast that could easily overwhelm a novel only strengthens the series's verisimilitude. Animation allows for designs and effects that would prove challenging to reproduce in real world contexts (though advancements in CG effects have so blurred that line as to present more of a budgetary rather than practical hurdle for live action these days).

The bottle society formed by the crew of the Ryvius provides the same microcosm study of human culture and societies that Golding's island did. But the extra depths of characterization make the dynamics at work behind the social constructs all the more understandable - and, in that way, both more beautiful and more terrifying.

Monday, May 20, 2013

Can a Story Change Your Life? - Aiming to Misbehave: Joss Whedon's Serenity

The way I came to Joss Whedon's motion picture Serenity diverges from the path traveled by most Browncoats. I never caught a single episode of Firefly during its abortive span on Fox. I saw its televised trailers and dismissed it as another shallow Hollywood amalgam of the science fiction and action movie genres. Its opening fell on the day before I was set to take the LSAT. Serenity had all of that going against it, yet I still ended up going to see it on Sept. 30, 2005. (And with the way law school and the bar exam worked out, it was the last movie I'd see for the next three years. Not that it would have mattered; no movie in that time - or since, really - has come close.)

Why? Because after months of LSAT prep, I was craving a really well-crafted story - and OSC himself had vouched for it:

I'm not going to say it's the best science fiction movie, ever.

Oh, wait. Yes I am.

....

If Ender's Game can't be this kind of movie, and this good a movie, then I want it never to be made.

Like most of his fictional recommendations, he wasn't wrong.

*

It's precisely because I wasn't familiar with the characters, milieu, and goings on of Firefly heading into the theater that I felt well situated to assess it as a self-contained story. The introduction provides everything you need to understand the core dynamics of Serenity's 'Verse, and the central conflict that drives the entire movie forward. The first scene with Serenity and her crew proper - along with being a technically impressive minutes-long no-cut take - is a masterclass in showing rather than telling: it gives the audience an immediate and intuitive understanding of who each crew member is, their role, and their relationship with one another.

In part the clarity of exposition - a true achievement in either the sci-fi or action genres - is the product of Joss Whedon's airtight writing. The man is one of the sharpest dialogue wordsmiths working the silver screen today (though he did lapse on some parts of the generally sharp and witty banter in Marvel's The Avengers, Exhibit A being Hawkeye's lead-weighted clunker in the midst of the Manhattan climax: "Captain, it would be my extreme pleasure." (emphasis added). If the line couldn't stand without the unhelpful adjective, it should have been rewritten from the ground up). Whedon is in top form in Serenity, where the 'Verse's eclectic English/Mandarin vernacular allows for a certain verbosity and playfulness that allows him to play to his strengths.

But fine-tuned banter is, in the end, merely icing on the cake. The heart of any story is meaning - the deeper, subtler doppelganger to the "theme" label that English classes often bandy about and slap ad-hoc onto a story like a price tag - in particular the meaning directly derived from the actions and interactions of the characters. In Serenity, the central meaning of the story resonates not only for its core conflict, but for the life stories of its main characters, and even - though I had no idea at the time - for the entire roller-coaster, underdog, and polemical experience of Firefly's fans themselves. It's meta on a whole other level, if you're inclined to go down that rabbit hole, but doesn't do anything to call attention to its depth. It doesn't need to, because it works at whatever level the viewer approaches it.

Monday, May 13, 2013

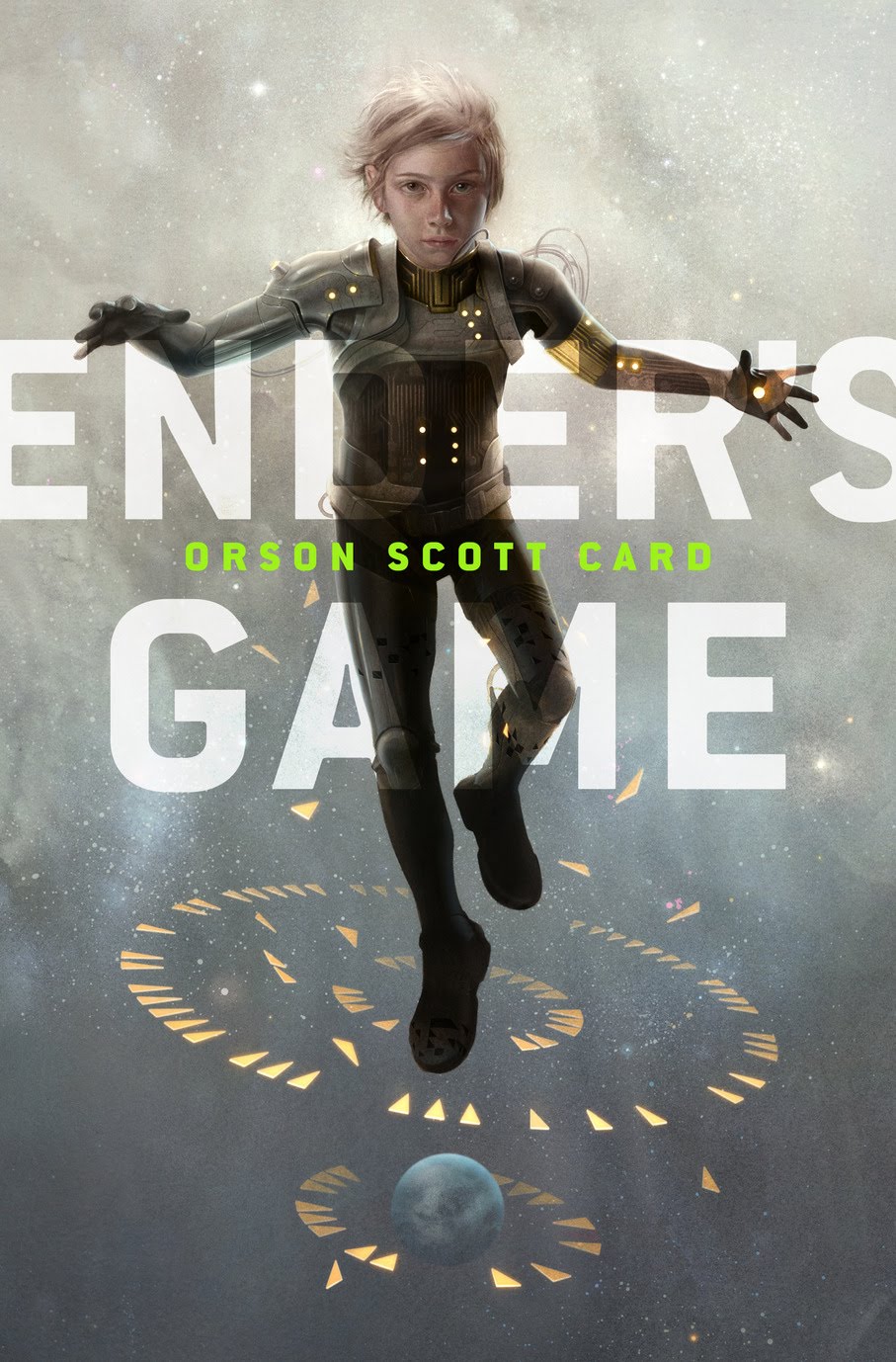

Can a Story Change Your Life? - Ender's Game, by Orson Scott Card

If I had to identify the book that exerted the greatest

influence on my decision to become a fiction writer, it would have to be Orson

Scott Card's Ender's Game. Much like Alfred Slote's C.O.L.A.R., from last week's Can-a-Story-Change-Your-Life? (or CASCYL for short . . . sounds like "castle?") post, it hit several of my personal interest points: child geniuses, strategy

games, interstellar warfare, and the philosophy of war. But what gave it

such a profound and lasting impact was how it took those elements and interwove

them into a deeply compelling story that centered, more than any story I'd come

across before it, on character, and really getting you inside his head.

The science fiction elements, though robust and well-realized on their own,

in truth served primarily as tools to allow the reader to delve deeper into the

protagonist's mind. Much like the monitor device introduced in the

novel's opening pages allowed Ender's observers to gain a thorough enough

understanding of him to make him the linchpin of their war plans, the course of

the novel makes the reader so invested in Ender that the wonderfully

orchestrated climax scores a direct emotional impact. The reader experiences

precisely the same reaction that he does in rippling waves of exhilaration,

disbelief, and latent horror - the very essence of catharsis. The ironic - perhaps even tragic - truth that Ender comes to realize of his various enemies in the novel resonates with the truth that the reader comes to realize of him: just as his understanding of them grows to the point where he both comes to love and destroy them in the same bittersweet stroke, the reader's understanding of Ender grows to the point where the reader comes to love him even as he undertakes the very actions that profoundly alter - and, in that way, destroy - the very person the reader has come to know. Although Ender endures the novel's events, he is, like the mono-mythic hero, changed by the experience, and the boy that the reader has come to know in the course of the novel is lost forever. The fulfillment of understanding concurs with the echoing ache of that bereavement, and the resulting amalgam of emotion and reason far exceeds the sum of its parts.

This kind of deeply personal connection with story and character is, I think, only possible in the fixed media realm (sorry, film, TV, and anime): specifically, novels and - I would contend - graphic novels. Those forms reliance upon written word - which is admittedly on a sliding scale when it comes to graphic novels - are what allow for the in-depth introspection that enables the kinds of character studies that allow you to experience another person's life as your own. This contention makes me view the upcoming Ender's Game movie with a certain degree of trepidation; divested of the advantages provided by the novel medium and OSC's direct storytelling prowess, will the silver screened story hold up to its written counterpart? Will what it gains in immediacy of action and bombast of visual and auditory effect make up for what it loses in interior thought and reflection? The storyteller in my suspects not; the eternal optimist hopes it will.

Monday, May 6, 2013

Can a Story Change Your Life? - C.O.L.A.R., by Alfred Slote

As I'd planned on approaching this series chronologically, I began this entry by searching as far back in my memory as I could for first story that gripped me long after I'd read it cover to cover and had set it aside. It may be that I'm forgetting something that came earlier - something that influenced me so subtlety and formatively that I can't even remember it - but when I searched for the earliest story that should feature in this series, Alfred Slote's C.O.L.A.R.: A Tale of Outer Space (1981) immediately sprang to mind.

In fiction market parlance, C.O.L.A.R. is a chapter book: shorter than a novel and embellished with full-page illustrations interspersed between the prose. As might be guessed from any title containing a punctuated acronym - especially one from the 1980s - it's science fiction. As the middle book in Slote's "Robot Buddy" series (inaugurated with My Robot Buddy in 1975), C.O.L.A.R. predictably centers around a secret colony of androids which is happened upon by the Jameson family, including the viewpoint character Jack Jameson and his robot-buddy-turned-brother Danny. The tensions arising from this inciting incident are predictable - but in a story intended for 6-12 year olds, this is perhaps more of a virtue than a vice - and well-positioned to test the core relationship between Jack and Danny that underlies Slote's entire series.

Although I would defend C.O.L.A.R. as a fine example of what a chapter book should strive to be, it would be a stretch to say that so simple and straightforward a story should have the inherent potency to make a person better simply for having read it. Instead, its place in this series is earned not by its intrinsic attributes, but rather by its effect on the reader - in this case, me.

Even in grade school, I craved stories about human-like robots and androids. I suppose those tropes more than any other were why I naturally gravitated to science fiction as a genre. But at least at my school and local libraries, stories featuring androids aimed at a younger audience were very hard to come by. Finding C.O.L.A.R. - which I found before My Robot Buddy or the other books of the series - opened my eyes to the possibilities, and gave the first satisfying scratch to an itch I, until that point, hadn't fully realized that I had. At least part of the impulse that led me to begin writing stories of my own were rooted in the fact that there weren't enough stories already out there that fit my personal list of top-tier criteria.

But beyond checking off so many boxes from my list of favorite tropes, I think what made C.O.L.A.R. resonate so deeply might have been its optimistic take on a question that has dominated the robot trope in science fiction: When humanity makes machines in its own image, how will it treat the darlings of its genius? And how then will our creations regard us, its creators? The trope of robots who rise up against their creators is a staple of science fiction, and C.O.L.A.R. taps into that tradition. Yet it subverts it by strengthening the notion of those robots as humanity's children - the robots of C.O.L.A.R. are actually made to look like and act like human children - and proposing that, as with real children, both nature (or design) and nurture (experience) have a role to play in what they become. Those heralding an inevitable robot apocalypse might disagree, but I've long anticipated that the more perfected our creations become, the more they will be predisposed to resemble their creators, faults and all. The question, then, is whether we as a whole will cast ourselves in a positive or negative light. If, as I suspect, that our good outweighs the bad, the same balance will be struck in those who come into being from us - biological, technological, or otherwise.

In fiction market parlance, C.O.L.A.R. is a chapter book: shorter than a novel and embellished with full-page illustrations interspersed between the prose. As might be guessed from any title containing a punctuated acronym - especially one from the 1980s - it's science fiction. As the middle book in Slote's "Robot Buddy" series (inaugurated with My Robot Buddy in 1975), C.O.L.A.R. predictably centers around a secret colony of androids which is happened upon by the Jameson family, including the viewpoint character Jack Jameson and his robot-buddy-turned-brother Danny. The tensions arising from this inciting incident are predictable - but in a story intended for 6-12 year olds, this is perhaps more of a virtue than a vice - and well-positioned to test the core relationship between Jack and Danny that underlies Slote's entire series.

Although I would defend C.O.L.A.R. as a fine example of what a chapter book should strive to be, it would be a stretch to say that so simple and straightforward a story should have the inherent potency to make a person better simply for having read it. Instead, its place in this series is earned not by its intrinsic attributes, but rather by its effect on the reader - in this case, me.

Even in grade school, I craved stories about human-like robots and androids. I suppose those tropes more than any other were why I naturally gravitated to science fiction as a genre. But at least at my school and local libraries, stories featuring androids aimed at a younger audience were very hard to come by. Finding C.O.L.A.R. - which I found before My Robot Buddy or the other books of the series - opened my eyes to the possibilities, and gave the first satisfying scratch to an itch I, until that point, hadn't fully realized that I had. At least part of the impulse that led me to begin writing stories of my own were rooted in the fact that there weren't enough stories already out there that fit my personal list of top-tier criteria.

But beyond checking off so many boxes from my list of favorite tropes, I think what made C.O.L.A.R. resonate so deeply might have been its optimistic take on a question that has dominated the robot trope in science fiction: When humanity makes machines in its own image, how will it treat the darlings of its genius? And how then will our creations regard us, its creators? The trope of robots who rise up against their creators is a staple of science fiction, and C.O.L.A.R. taps into that tradition. Yet it subverts it by strengthening the notion of those robots as humanity's children - the robots of C.O.L.A.R. are actually made to look like and act like human children - and proposing that, as with real children, both nature (or design) and nurture (experience) have a role to play in what they become. Those heralding an inevitable robot apocalypse might disagree, but I've long anticipated that the more perfected our creations become, the more they will be predisposed to resemble their creators, faults and all. The question, then, is whether we as a whole will cast ourselves in a positive or negative light. If, as I suspect, that our good outweighs the bad, the same balance will be struck in those who come into being from us - biological, technological, or otherwise.

Wednesday, May 1, 2013

Illustrating Resource: Wacom イラストレーター Live Painting YouTube Videos

Today's resource post highlights a playlist of "live painting" videos that Wacom has posted to YouTube using its "wacomcl" user account. These 30+ videos, each speed up several times to condense hours worth of work into minutes worth of video, show several well-known Japanese anime-style artists creating illustrations from sketch to finished piece using a Cintiq monitor (which would be Wacom's pecuniary interest in making these videos). The real value in watching these videos is the unique insight they can give into the work processes of the individual artists, and how much variety in approach and technique exists among them - points of differentiation that contribute directly to each artist's distinctive style.

On an even more basic level, it can reassure an aspiring artist to see that even professionals whose work appears on book and game covers and even large advertisements in Japan draw their amazing illustrations one line at a time, and even resort to erasing when the lines they've laid down aren't quite working. In this way, these videos have a similar benefit to those posted by Brandon Sanderson: they offer a peek at the actual act of creation for artistic works that, when viewed solely as a finished piece, seem superhuman in achievement. Witnessing these creators do what they do to realize their works is both awe-inspiring - the skill and aesthetic eye involved is apparent even at break-neck speeds - and encouraging.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)